Blog

Relearning School: An Educator’s Social Justice Journey

By: Instructional Coordinator, Maria Wahlstrom

I remember feeling terrified to misread out loud or say the wrong thing in class, and worse: I remember if my test answer was marked “wrong,” I would feel my stomach sink along with the corners of my mouth. I remember “good students” and “bad students” and trying to figure out which one I was.

I remember thinking there was one answer to my question, and the teacher usually had it.

I remember associating red with “bad” as I watched my mistakes turn red.

I remember fearing mistakes and forgetting their inevitable nature.

I remember annoying subtle giggles echo my “silly questions,” (which I really wanted to know).

I remember purposefully staying silent to avoid my teacher’s response.

Yes, I guess I had a reason to be afraid, not of school, but of mostly being wrong; of thinking differently.

I now realize that my school actually taught the same lesson every year: there was a predefined box called intelligence, and all I had to do was find my way in it.

Coming from a privileged background of educated parents and consistent support, I somehow made it down the path of education. It wasn’t always easy for me, but everyone I knew pushed me through. Eventually, not only did I learn the rules of the school game, but I was lucky to learn to play it well. I believed winning would reward me with labels known as, “smart” or “successful.”

This prize would make me worth something. Isn’t that what we all learn in school? I believed in the game; I eventually succeeded in the game (even when it wasn’t easy to play). With privilege, I was able to squeeze tightly in the box. I learned the “right answers” of mainstream school of thought, so I began to see more red A’s than red mistakes. I knew the “intelligent answers” without question.

I learned to primarily value efficiency, without realizing its potential interference with human experience and equity. I learned success was school leading to money, so I too bookmarked these goals into my mental life trajectory. Yes–school turned out okay in the end–and I learned a lot. As a kid, I didn’t question what I learned; I didn’t dare question my teacher; or how school was implemented.

Once I eventually found my way into the prize box, I didn’t critically think about it. After all, I didn’t see the need.

The Turn. But looking back, this journey through and to “intelligence” coupled with my work at Village Leadership Academy (VLA) has now led me to question much of what I know. It has made me rethink the traditional path and find new ways of educating.

As a first year teacher a few years ago, I too believed traditional education worked because it somehow worked for me. I naturally forced it onto my students, in hopes that I was helping. But, I was increasingly disappointed to see that it didn’t produce independent and inspired thinkers/learners (despite their academic growth on test scores). So I gave the famous college talk, in hopes that it would trigger motivation. “If you do well in school, you can go to college and get a good job!” I enthusiastically told my kids. They replied with blank stares. To them, going to Chucky Cheese or Pump it Up was more inspiring than going to University. Although I still believe emphasizing college is important, it was clearly not enough.

There were deeper problems the college talk could not completely address. Aside from some challenges outside the classroom, I noticed challenges within the classroom as well. First, students didn’t seem to “independently think” on test– which asked them to regurgitate information in a systematic way. Next, they didn’t always seem engaged with the text or context–which seldom represented their identities, cultures, or experiences.

Furthermore, it took forever to get kids to want to share their independent ideas–in a classroom environment that predominately labeled silence as good behavior. Despite these limitations, outsiders would claim they were somehow “becoming smarter.” From a quantitative perspective, the test scores suggested they were improving at a good rate. Qualitatively, I quietly observed incremental problems with this traditional classroom. The numbers seemed right, but something else was missing. The path may have been producing readers and writers, but it wasn’t producing the inspired leaders our school and their communites demanded.

Village Leadership Academy challenged me to ask two questions: Should I force it? or rethink it? Little did I know I was about to embark on a new challenge: I needed to relearn school and team up with VLA to help rebuild a different school that works–for the population we teach.

More than ever, our kids needed to learn how to identify and face social, economic, and political injustices that started the achievement gap in the first place. We could not perpetuate these systems in the classroom and expect to “close the gap.”

No wonder our Chicago achievement gap “hasn’t closed within the last 20 years” (according to the University of Chicago’s recent findings). We are trying to fix the problem with another problematic system. We rarely step back to critically evaluate whether or not we may in fact perpetuate these same systems in our teaching without knowing.

We are educating kids who remain marginalized in American society and label them as “deviant,” but we hardly equip them with the empowerment and innovative skills needed to create their own change and confront injustice (or understand how these systems of injustice can follow them their whole lives, even after college). Instead, most schools equip students with increasing amounts of information and predefined procedures rather than actual thinking skills. They hope the consequences of injustice will change once students learn the information and leave their communities. But, it is too easy to indirectly emphasize to our kids that they should leave their communities rather than help rebuild them. It became incrementally evident that VLA had an important point overlooked in most education policy discussions: Social Justice is needed as much as Reading, Math, and Science. This had to be the foundation for school systems, educators and students.

The New Road. I would love to take you– as the reader– through the rest of this mental journey of “relearning school” (a journey that has occupied my mind for the last couple of years at VLA). However, the process has been long, ongoing, enlightening, frustrating, and not to mention: uncomfortable. It has pushed me to think outside of norms–outside of my own privileged experience–and refocus on the underlying implications of schooling, especially for children of color. This journey has been marked with long debates, subsequent mistakes, periodic successes, some research, and (honestly) the journey hasn’t ended yet.

Nonetheless, the realizations I have acquired so far are worth noting. As I experienced this journey of relearning school, I began to realize the box of “intelligence” and the path of education was too narrow in traditional elementary schools. Not only did I learn the importance of social justice education (from my school, my experience, and various influences), but I am also learning what it entails. Specifically, here are a few thoughts I have gathered along the way:

1) A Social Justice Education goes beyond test standards: it encourages children to critically think and never fear wrong answers. While an emphasis

on testing encourages thinking in the box, an emphasis on social justice encourages thinking outside of it. As one teacher stated in this Huffington Post article, “When we teach or model the expected process, we set up outcomes that determine a child’s thinking.”

Through traditional schooling–which primarily emphasizes testing–children already sense that there is probably a correct answer you may be looking for. Children learn to look for correct answers and procedures before exploring the beauty in different and possibly “wrong and new ideas.” (Note: Now, I am not saying there is no such thing as a “correct answer.”

I am just noting that it is also important for students to explore their own thinking process than sprint ahead to a predefined destination–which usually results from an overemphasis on testing).

It is important for educators to allow students to do the work (the thinking) and not fear the process or mistakes along the way. After all, this is usually the reality of real world problem solving. Students should develop their ability to see many ways of doing things, rather than one.

Feeling confident to think outside the box, whatever box that may be, is a skill within itself. When they navigate this process, not only are they able to know what they think, but more importantly, why they think it. We must create a classroom environment that allows kids the space to practice listening to each others ideas, forming their own ideas, articulating them, defending them, and having the courage to abandon them for something even better.

This is when learning truly becomes their own process and journey. In a social justice classroom, critical thinking is the focus, and fear is the enemy. After all, aren’t social justice concepts born from thinking outside the norms?

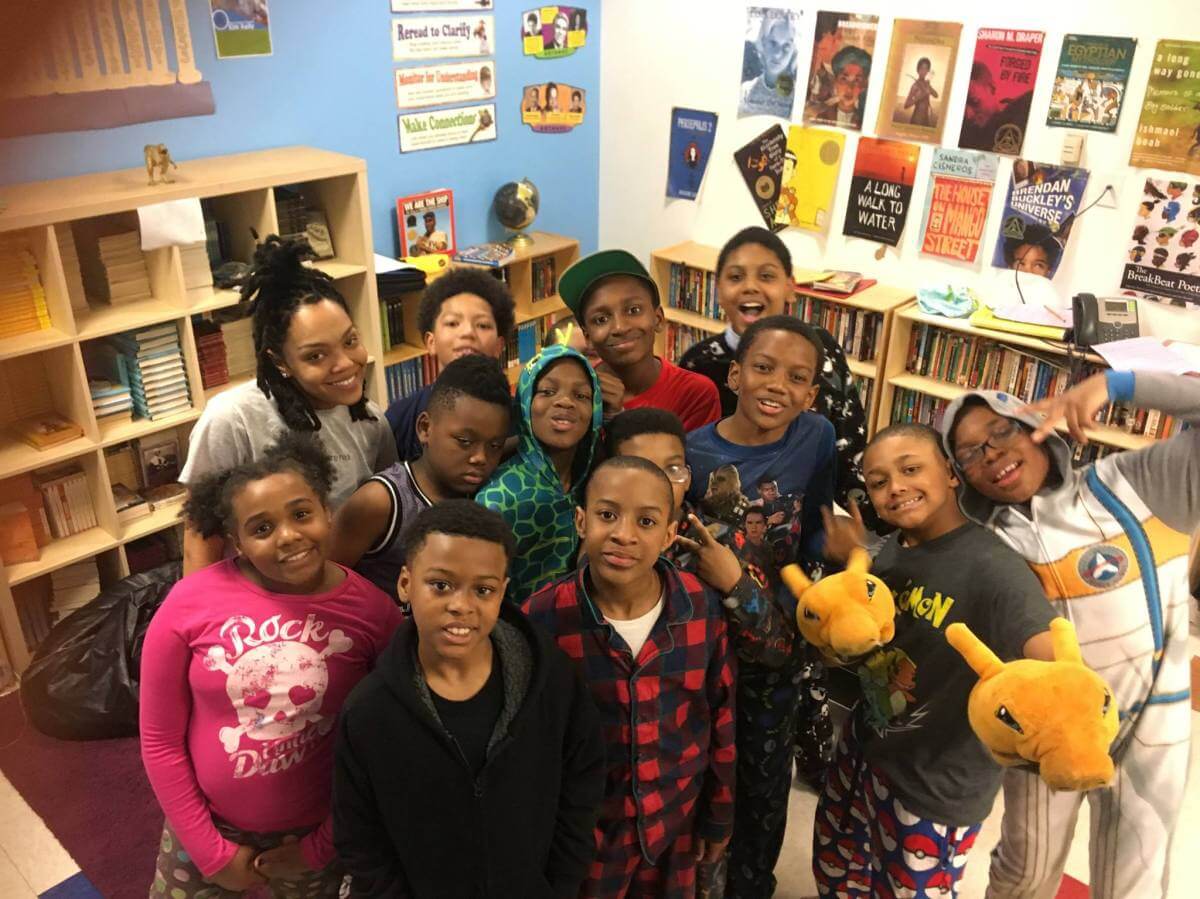

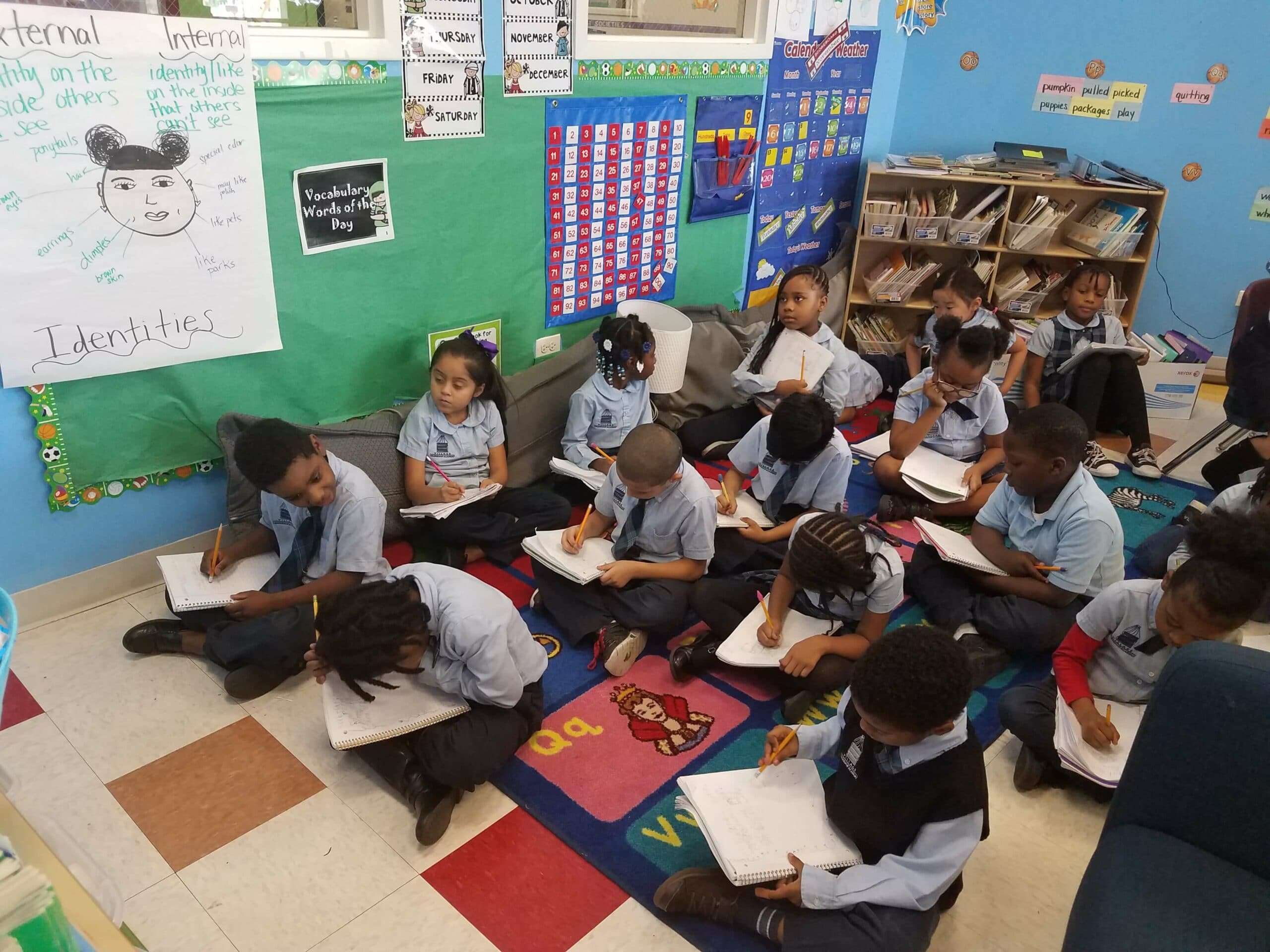

2)A Social Justice Education goes beyond first month introductions: it emphasizes identity all year round and constantly encourages children to use every context to help them have a deeper understanding of themselves.

While traditional classrooms may limit identity topics to the first week or month of the school year, a social justice classroom emphasizes identity all year round. It places students as the center of their own learning. This type of educations asks them to constantly find ways to relate to what they learn. For example, rather than identifying only mere facts, they reflect on:

1) how do these concepts shape them?;

2) what can they learn from these concepts in their own lives?;

3) how can they further these concepts to benefit the world? They not only learn subjects, but they also learn how those subjects affect who they are and what they can do.

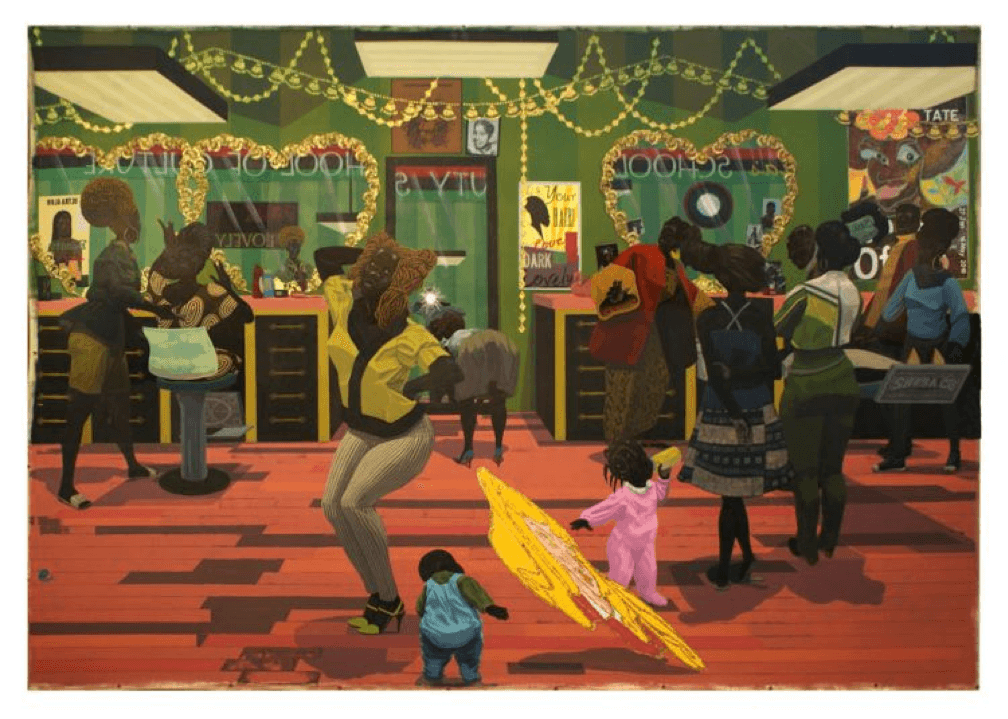

3) A Social Justice Education goes beyond eurocentricity: it emphasizes global history, perspectives, cultures, and current events of every region. It takes a holistic approach on viewing the world, its history, and its cultures. If you look through world history textbooks, you most likely find the majority of chapters are allocated to Europe and America and written from their perspectives (Loewen). For example, the title such as “Discovering the New World”– which implies the area was only “new” to those who did not already reside in the region–clearly gives a limited one-sided viewpoint of history.

This skewed eurocentric view of world history has limited our knowledge on the rest of the world. We do not want our students to learn only one type of history (which was never told from the perspectives of their heritage and culture, and certainly not in the interest of it).

Teaching a holistic global story using multiple perspectives is important to social justice education because it increases the likelihood of cultural understanding and respect. It also allows children to see how oppression and social change manifest themselves differently throughout time and throughout all regions of the world. If ignorance is one prerequisite for injustice, then we must not perpetuate cultural and global ignorance within our classrooms.

As Linda Salvucci, the vice chair of the National Council for History Education, recently stated about traditional social studies classrooms and curriculum: “People tend to think that history is only memorizing facts. More importantly, it is a way of thinking and organizing the world.” With this point in mind, we cannot stay divided as citizens of the world while memorizing one-sided facts and perspectives.

Rather, we must seek to understand and respect (even if we don’t agree with) other perspectives, experiences, and lessons before we can truly seek peace. We should allow our students to do the same.

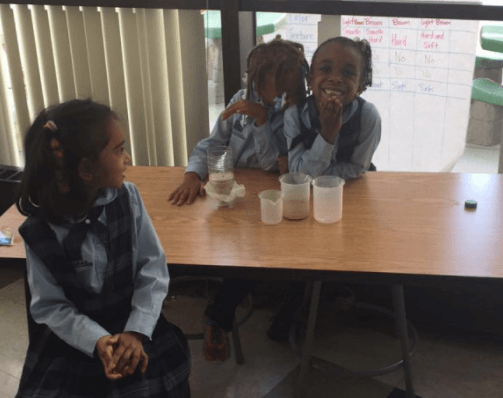

4) Social Justice Education goes beyond silent classrooms: it empowers children to speak up and collaborate. Social justice learning is NOT a quiet process.

It encourages thought provoking student-centered discussions and allows students to deeply question (to the best of their ability) what they think, hear, and read. Instead of silent and teacher centered classrooms, social justice classrooms are loud because students lead discussions with questions and thoughtful responses.

Students work collaboratively to find answers or rethink what they know. They ask questions during reading, and they are encouraged to identify perspectives during any event.

Teachers facilitate the uncovering of critical learning and relearning, rather than dictate it. The classroom emphasizes that knowledge is never finite, answers remain relative (depending on perspective), and seeking justice is an ongoing process. Thus, classroom discussions are fluid, challenging, and never silenced.

5) A Social Justice Education goes beyond classroom walls: it gives children opportunities to utilize skills and knowledge outside the classroom and apply it to the real world. Rather than only giving the traditional message of “learning will be important later in life because it will help you go to college,” social justice education gives the additional message that “you can develop your skills by using what you learn now to help make needed change.”

Social justice education should not only discuss culturally and socially relevant issues that students face, but it should also give them opportunities to problem solve through these issues with social action (or service learning projects). Rather than talking about hypothetical word problems, children think deeper about real problems they observe or experience. They practice problem solving in real life situations through various subject areas. When children see how they are important to the world through social action, then they begin to believe in themselves and the potentials of their learning. They start to feel important and understand their own value.

Looking Back. Perhaps we all need to constantly reflect on what, how, and why we teach. Let’s start with ourselves as educators and uncover social justice in our own teaching. As social justice educators we need to question the systems of our teaching.

We need to be mindful that we are not perpetuating the same messages of being quiet and fearing “wrong answers.” Educators, even with best intentions, can still easily miseducate if they are not always reflecting on the implications of the structure and systems that define, and can consequently confine their classroom environments.

Although I have learned a lot at VLA, I am still relearning education. I have started to see the need for different ways to educate and empower. My passion for social change has widened while working at VLA– not only for change in the world, but also for change in the way we practice as educators. When you are pushed to relearn education, you start to realize the new path may feel bleak at first, but it is possible and even necessary.

This journey begins once we have the courage and the drive to make the turn.

Enroll Now

Discover a partner in the future of your child. Enroll your scholar for the 2021-2022 school year today!