Blog

Interview with VLA Principal, Dayo Harris, on Social Justice Education

By: Tara Shedor, Director of Communications

Many people who have heard of VLA are familiar with the World Scholars Program and the GrassRoots Campaigns. Can you explain how those two programs work in tandem to help prepare future world leaders?

Ms. Harris: With the GrassRoots Campaigns, students are asked to think critically about their communities and about a social justice issue or inequity that they are experiencing or see others in their community experiencing. They spend the year researching the root causes of the identified issue and learning about influential forces and power structures and ultimately develop their own action plan which they are expected to implement.

Through that process, they are also looking to see if other individuals or organizations are working to address the issue. Because we are an independent school, we have the autonomy to invite various community activists and organizations into our learning space, so we encourage our students to be in conversation with folks who are taking initiative and who are community leaders to learn from them and their own ideas as well.

We never want our students, who if we look at them demographically are coming from areas that are resource depleted, to look at their communities and think that there is some sort of inherent cultural pathology or something that is wrong with their community or people residing within their community. We want them to understand that there is an inequitable system in place and that the answers needed to improve the community come from us– from the community itself. We want our students to learn that lesson early on and to get practice working in solidarity and being positive change agents now.

They have voices, and they are able

to be active and empowered now.

Ms. Harris: So that’s the voice part. Chicago is one of the most segregated cities in the U.S., and because of that, we look at the disparities that happen between neighborhoods and communities. We want our students to understand why that is and to understand their role in making that better.

The GRC is the local component, and in terms of the World Scholars Program, we also want our students to understand they are part of a larger diaspora and that is important. If we are saying we want to help our students be global citizens and global leaders, we need them to experience the world now and understand how they are connected.

There was a lot of discussion at one point about when students should be eligible for the World Scholars Program (WSP). Now that it is 3rd through 8th grade, there are questions we have asked ourselves such as, “Is third grade too young? Will they really understand what they are experiencing?” Like many things with education, you have to give it time. You have to go back and do the check-ins and get the reflections and the data. We are finding out now because some of our first students who experienced the World Scholars Program are in high school and college, and they consistently refer back to those experiences and how they enriched their learning and expanded their background knowledge. It continues to reshape and form their worldview and how they perceive things. They feel privileged that they had such an experience at such a young age when they are engaging in conversation with their peers and teachers.

Unfortunately, some of our former students are interacting with educators who have misinformation about cultural groups or countries or communities, and our students are able to say, “Actually, I was there. I was on the ground. I know what it feels like,” or, “I was able to meet the Minister of Education in The Democratic Republic of Congo and these were the issues…,” I think that our GRC coupled with the WSP helps to develop our students holistically.

How does the VLA experience empower students

to think critically about their own education?

Ms. Harris: That’s a good question. I think some of the benefits of being an intentionally small learning community is that we are able to maintain small classroom sizes, engage in really honest and transparent conversations with our students, and to center the he mission of the school while remaining aware of our short and long term objectives. We want our students to feel culturally empowered and to be critical thinkers, but we also want them to be enactors. We want them to be people who act, who are proactive, and who are not passive.

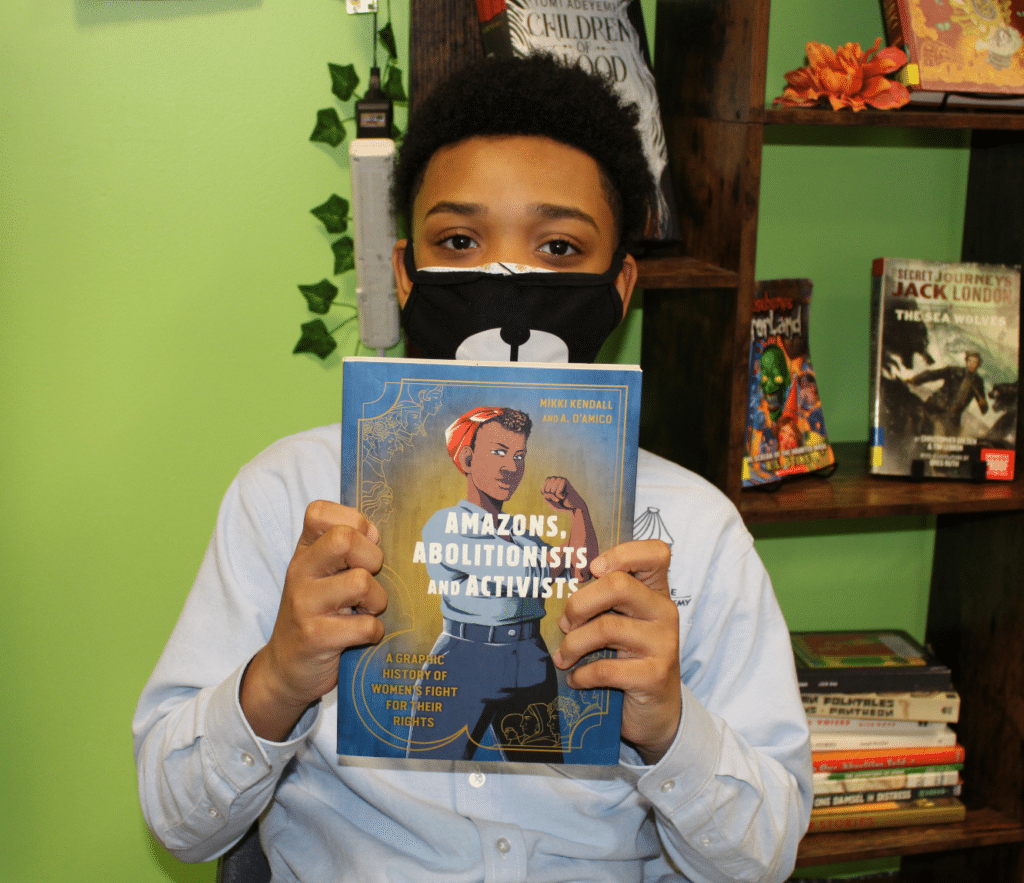

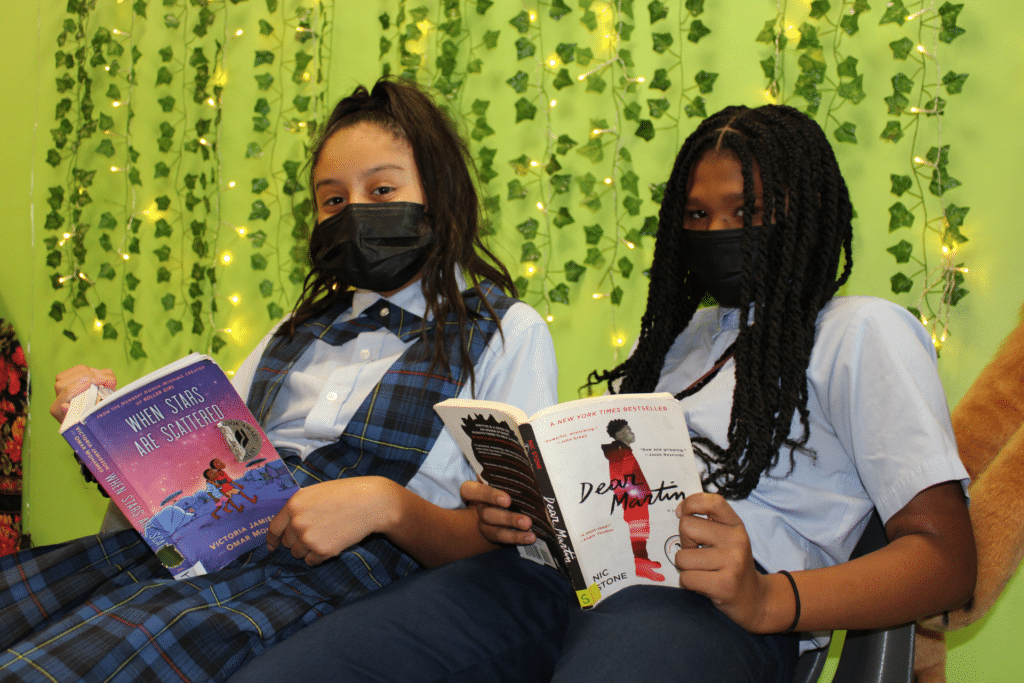

For this reason we focus on the intrinsic motivation of our students as well. We understand our students come to us with a vast knowledge base. In our field, we call that “funds of knowledge” and want to be utilizing what students already know and ensure we are providing a curriculum that is culturally relevant and culturally responsive enabling our students to identify with the text and content they are reading and the concepts that they are learning.

The discourse that is happening in the classroom is important too. We want to be sure that we are giving space for student voice and student experience and using that to inform our curriculum and to inform the lessons that are being taught. Of course we have Common Core and state standards, and there are certain other requirements that we have as a school, and it is our responsibility to meet the criteria and add our VLA style by digging deeper through critical questioning. It is not always easy, and I’m not saying we get it 100% right all the time, but our intention is there, and we continue to get better at it.

When you were describing how VLA appreciates the unique background that each student brings, you said you call it something– “funds of knowledge?”

Ms. Harris: Oh yeah, that’s an education term, “Funds of Knowledge.” Basically, it’s the idea that students come to you with cultural knowledge already. For example, if we have a student who works in their family restaurant on the weekends or helps their parents, they are learning so much already– they’re learning a particular math and a certain business acumen. Students may have added responsibility depending upon the family household– you might help your mom with the budgeting or maybe your grandfather is a mechanic, so there are certain things that you are learning. It’s really important at the beginning of the year that teachers do something like a questionnaire or an interest survey that allows them to capture certain knowledge bases– both cultural and practical– that might be happening in the household or in the community so that those things can be used as reference points specific for that student and the class.

So then you would say that identity affirmation

is a big part of VLA curriculum as well?

Ms. Harris: Oh, absolutely! I was just reading something the other day that said that the age at which students and young people– people in general– start recognizing racial differences is really young! It’s like infants even! The research said by age four children begin to experience discrimination. They are aware they are being unfairly disadvantaged by their race or external identity. We also know–and there is so much research out there– specifically for Black children, because of the society we live in, they are being bombarded with negative images of Blackness, and so it is really important for us that we are combatting that and are positively affirming our students and their complex identities.

Race and ethnicity are certainly major components of student identity, so we want our students to be able to look around the room and see themselves being reflected in the texts that are chosen, in the artwork on the wall, and in the conversation being had in the classroom. The VLA student affirmation itself says, “I am young, strong, and proud. I love myself, my family, and my community.”

We understand love

to be an action word.

Ms. Harris: It’s really speaking about what that means. What is our sense of responsibility around that? I think we have some of the most confident students here in the city of Chicago. I think a lot of that confidence comes from– not just from them being encouraged to use their voice– but VLA being a positive space where they see themselves readily reflected and encouraged to be their full selves. Like I said earlier, they are culturally affirmed in who they are, their background is acknowledged, and they’re encouraged to can come in and share, soo it’s about creating that space.

So would you say then that identity affirmation ties

into leadership development as well?

Ms. Harris: For sure! We also have a class called Tabura which teaches from an ancient African ethos. There is also a somatic component to it. It’s about character development and asks you to think deeper about what it means to be part of a community: What are the necessary skills that I inherently have? What skills must be developed for me to be an upstanding member of this community? I certainly think identity affirmation and leadership are related. It’s not just students attempting to be the best version of themselves, but it’s also about really reaching their full potential and using their talents to improve our communities. Through Tabura instruction there is an expectation that you are stepping up and that you are speaking up and acting in positive, disciplined ways; and through that, students are developing leadership skills as well.

It sounds like VLA also has a great emphasis on creating a safe space for students to express themselves fully.

Would you say that this is something students have really appreciated?

Ms. Harris: I think so. You know, that comes at a cost at times. When I said that we have some of the most confident students– it hasn’t happened yet this year as far as I know, but that could look like students questioning teachers around content and asking questions such as, “Why did you choose this particular book?” or questioning a method that they are being taught. I think that it is important for students to have those conversations with teachers as well.

We also have a family interview as part of the enrollment process, and we do ask very specific questions around how comfortable families would be with us engaging in conversations about race, class, gender, etc. with their children. What has been reported repeatedly by families with students at VLA is that their dinner conversation changes and that their children begin to question them by asking things like, “What are you doing to improve the community? Were you active on campus in college? What social concerns did you have in high school? Did you have the opportunity to learn the things that we are learning?” I think parents really appreciate the interest their children are taking in social justice issues, and we also know that it takes courage to speak out and ask such questions.

I know that I personally speak to students about courage and accountability a lot… Using your voice takes courage and so does acknowledging a mistake. If you make a mistake, be accountable for that. Say, “I’ll do better the next time.” You can’t just talk about leadership skills in this vacuum–educators have to model it and students have to have space to try it on. I ask, “What did it feel like when you advocated for yourself directly? When you told your peer, “I don’t appreciate the way you’re speaking to me right now,” what did you notice within yourself? What did it feel like in your body? These are some of the conversations I’m having with students.

I think I see the school, the classroom, and what we are doing with the GRC curriculum as testing ground for students to try things on, to dig deep into their courage, and to actually apply what they are learning. They get to see what it feels like taking on a social cause. They get to the point where they are so confident they are beginning to question and think critically about the readings their teachers give and how they relate to their growth and development.

Ms. Harris: I’m actually recalling a conversation I had with a 2nd grade teacher, Mr. Reed, last week, about how we have a new literacy curriculum–some of which is scripted– that we need to be mindful of making “VLA style.” Teachers are expected to read ahead, obviously, and to know when and if things need to be supplemented or certain topics or concepts need to be explained differently. I think the particular text they were reading was about the U.S. Constitution, and the artist illustration in the book showed two people voting– one was a person who looked Black or of African descent and the other was a white women. His illustration is supposed to be a depiction of voting participation around the time of the initial framing of the Constitution, which we all know for a fact during that time period women did not have the right to vote and neither did Black people.

He said, “I’m looking at this text, and we’re talking about the Constitution, but I’m seeing this picture, and I felt that it was important for me to explain the issue to our students.”

We wouldn’t want our students to be confused later on about the fight for voting rights and the segregation of Black people and for them to have the image where they saw a Black person and a white woman voting as if they had never been excluded from the Constitution. That’s just an example of some of the conversations we have to engage in while teaching our students how to critically read and examine texts. It is important to know history, and anyone looking at this picture could easily misconstrue what actually happened historically. Again, that’s just an example of the conversation VLA teachers are having with students, and it’s not pointed out in the curriculum anywhere. The problematic illustration wasn’t expected, but he noticed it, and because of our school culture, it became important for him to point that out. I’ve asked Mr. Reed if he would be willing to write a blog about that, and he said yes. I need to follow up with him because I think moments like that are important.

Social justice isn’t always this big appealing or provocative thing. Sometimes it’s, “Hey this picture doesn’t match what was happening historically, so we need to take the time to talk about it.”

On that note, I am sure there are other educators that may be looking for additional resources for designing their own curriculum. Could you identify a couple?

Ms. Harris: Sure. I think first and foremost, in this unique moment in time, if people haven’t read Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, I think you definitely want to read it and also An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Rethinking Schools also has great publications and resources on their website and so does Facing History and Ourselves. Teaching Tolerance, which is now called Learning for Justice, is also an awesome resource for educators. I think these are all good starting points with a host of ideas, lessons, and resources, but I think that it ultimately starts with ourselves first. Many of us have been miseducated, and it’s about relearning, unlearning, and discovering different perspectives. Educators have to put in the work and learn to become comfortable with being uncomfortable and even angry once we’ve realized just how much we’ve been intentionally miseducated.

Oftentimes, when we talk about the problems within education, people want to look at the urban communities. I think there is a gross injustice being made across the board because many schools refuse to teach American history accurately, and there is a reason for that. I think when we start exploring those reasons that it doesn’t necessarily have to be a negative, disempowering experience. It is a project of truth telling, and until we are able to do that, we will never be able to fully validate and heal from what has happened here on these lands historically, and we are going to continue to have these conversations, tensions, and violent conflicts for generations until there is the full reckoning– it’s kind of like the individual, right? When we ask an individual if they’ve made a mistake, we want them to be honest and take accountability, right? We understand that the individual will continue to evolve as a person, but we don’t expect them to continue to make the same mistakes. We can work with that.

It’s sort of how we perceive history in the same way. The United States government hasn’t taken full accountability for its historical actions, which prevents the necessary validation and healing so that generation after generation continues to have these backlashes, and I think it’s exhausting. I feel exhausted by it. I really do hope that we are on the precipice of something more radical happening within schooling in the U.S., but there is a lot of resistance to calls for disruption and innovation that center truth-telling. I think that is one of the crises in education right now that we need to work around, and that starts with the individual who understands they are part of a collective.

This has been great talking with you today. Any final words for those might be coming across this blog on the internet?

Ms. Harris: Sure. Final words of advice. I think, at best, education should be a transformative experience for both students and teachers. We have to get comfortable with being uncomfortable and understand that this work is about social change. Get comfortable with unlearning and relearning. It’s going to be messy. Nobody is expecting you to be perfect, but we do expect you to be profound. Remember that it is a collaborative experience and that you want to intrinsically motivate your students. The best way you can do that is to be your authentic self in the classroom.

M. Ekundayo Harris is the principal of Village Leadership Academy. She is a Teach for America alum with over ten years of experience in the profession and an extensive background in culturally responsive teaching, curriculum design and instruction, and educational leadership. She has provided strategic education consulting for administrative teams and school sites across Chicago and remains committed to addressing educational equity and the eradication of the school-to-prison pipeline. Harris received her EdM in curriculum and instruction from the University of Illinois Chicago and her BA from Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts, where she received both the Unity Award and the Juliet Evans Nelson Award for her contributions to the college. She is a proud board member of Sisters in Cinema, a nonprofit organization with an inclusive mission to entertain, educate, develop, and celebrate Black girls and women media-makers and future generations of storytellers and their audiences.